|

The following section focuses on the key elements of Central

Asian textile arts.

Motifs

Motifs are the distinctive figures featured in many art

forms. The motifs in Central Asian textiles are often abstract.

Abstracting motifs was essential because of the technological

limitations and constraints of flat weaving, ikat

and felts. Knotted pile carpets and embroidery allow greater

design freedom. Another reason for the wide use of abstract

motifs was that Islamic religion forbids the use of realistic

images, hence the images became highly stylised motifs.

The

ram's horn is a common and very ancient motif. Note the

ram's horns in Fig. 4. Floral motifs and patterns occur

in both nomadic and urban textiles, both naturalistic (suzani)

and stylised (rugs and ikats). Animal motifs are

common in nomadic rugs, as the nomads are still influenced

by shamanistic beliefs and not as heavily influenced by

Islam.

Fig.

4 Detail of Tekke Turkmen carpet.

Wool warp, wool and cotton weft float brocade, made

by Tekke Turkmen women in western Turkestan, late 1800s.

3120 x 1850 mm. 85/1900. Powerhouse Museum Collection. |

Repeating

motifs

Central Asian textiles, such as nomadic rugs and carpets

and urban ikats, are characterised by the use of

repeating motifs. The reasons for this are:

- repeating

motifs are easier to memorise

- ikats

entail repeats.

The

patterns formed by the repetition of motifs were memorised

by women and passed down from generation to generation.

It was easier to memorise a discrete motif and repeating

pattern than a free-flowing design. Rugs can usually be

attributed to a particular cultural group by the motifs

used.

Young

girls learn the skills of textile production from an

early age, under the supervision of an older woman,

and the designs used by their particular tribal group

are committed to memory over many years of training

and practice. By their early twenties, most young Turkmen

women are skilled weavers and those who have not yet

had children may expect to spend up to 12 hours a day

weaving. (Sumner, 1999:28).

Activity

Compare the motifs in the following two rugs. (Figures 5

and 6)

|

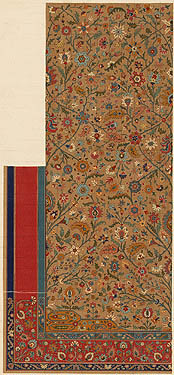

Fig.

5 Baluchi prayer rug

The weaver, a nomadic Baluchi woman, has used brilliantly

coloured silks for the 'trunks' of the tree motifs

in the central mihrab (prayer niche) and corner spandrels

of this rug. The influence of Turkmen design is evident

in the guls of the wide border surrounding the mihrab.

Wool warp and weft, wool and silk, asymmetrical knots,

made in north-western Afghanistan, about 1900. 1520

x 1030 mm. 96/39/1, Powerhouse Museum Collection,

purchased with the assistance of the Oriental Rug

Society of NSW, 1996.

|

Fig. 6 Mushwani Baluchi rug

Wool, symmetrical knots, made by Mushwani Baluchi

women in western Afghanistan, about 1900. 1880 x 1020.

Powerhouse Museum Collection. A8358.

|

The

colours used in nomadic textiles — browns, rich dark

red and blues — were darker and earthier than those

used by the oasis dwellers. Silk was available in the towns

and cities and lighter colours were often chosen. Silk was

a highly valued fibre.

Activity

Look at the detail in Fig. 5 Baluchi prayer rug. Note the

coloured silks used in the trunk of the tree of life.

Rugs

Three types of rugs are produced in Central Asia:

- knotted

pile

- flat-weave

- felt.

Rugs

and carpets are made in a nomadic context and also

in villages and towns. Village rugs are made by women

who were once nomadic, using the same or similar patterns.

These rugs are often larger and made for the market

place. Urban rugs were made by men in workshops on

fixed looms. The use of cartoons was necessary for

more complex patterns. Cartoons are drawings of the

same size as a planned pattern for a rug. It is used

as a model so the pattern can be transferred or copied.

See Fig. 7.

In

addition to making textiles for their family's own

needs, nomadic women produced rugs for sale to town

and village people, many of whom were once nomadic

themselves and wanted nomadic rugs for their permanent

homes.

The

shape, method of weaving, dyes, patterns, knot density,

and designs of a weaving all tell something about

the life of the weaver as well as its use. It tells

if she was nomadic or settled, which tribe she was

from, and the weaving's intended use. (O'Bannon,

1998: 11)

|

Fig.

7 Rug design from Iran

Fig.

7 Rug design from Iran

Paper, pencil and watercolour, painted in Iran, about

1920.

540 x 373 mm.

Powerhouse Museum collection 86/1715 |

Rugs

can be attributed to particular cultural groups and even

tribes within a culture by analysing the following characteristics:

- Type

of knot

- Type

of motif, in particular, type of gul

- Colours

- Warp

colour

- Weft

colour and fibre

- Edge

finish, for example, selvedge or overcast

- Knots

per square unit

- Fringe.

(O'Bannon, 1998: 25)

Felt

rugs

Central Asian felts are made by:

- placing

wool fibres in layers on a reed mat

- applying

heat and water

- compressing

the fibres by rolling up the mat then continuing to roll

the mat back and forth.

The

natural properties of wool allow it to felt quite easily.

Except

for yurt coverings, which are mostly white, felts are

generally patterned by several different methods:

Layering

This method can result in a felt with the pattern on one

or both faces of the felt. For one face, wool of a single

colour is laid on a reed mat in the size desired. Wools

of other colours are placed on top of the foundation wool

in the pattern desired. The resulting felt shows only

the foundation wool on one side and the pattern on the

other. For two faces, the variously coloured wools are

placed directly on the reed mat in the pattern desired.

The resulting felt shows the pattern on both sides. A

variation is to lay a coarse rope of wet, dyed wool on

top of the patterned area to create a secondary pattern.

When rolled in the felting process, the dye in the rope

transfers to the felt. After felting, this rope is removed,

leaving the pattern.

Mosaic

In this method, felts of different colours are cut into

pieces and sewn together to create simple or intricate

patterns. For some of the most complex patterns, two or

more large felts are made in different primary colours.

These felts are then stacked on top of one another and

cut into pieces, cookie-cutter style. If three colours

are used, the coloured pieces are reassembled and sewn

together, jigsaw fashion, into three felts of three colours.

Applique

In this method, pieces of felt or other fabrics are sewn

onto a finished felt to create a pattern.

Embroidery

In this method a felt in any technique will have an additional

pattern applied by embroidery. (O'Bannon, 1998: 16)

Fig.

8 Lakai Uzbek felt rug

Pieced and embroidered felt rug made by nomadic Lakai

Uzbek women in Southern Uzbekistan in the 1920s. Powerhouse

Museum Collection. |

Fig.

9 Lakai Uzbek felt rug detail

Detail: the embroidery stitches used to decorate the

Lakai Uzbek felt rug are similar to those used by urban

Uzbek women to embroider their suzanis. The filling

stitch is called basma, and is a form of couching.

|

Fig.

10 Lakai Uzbek felt rug detail

Detail: the back of the Lakai Uzbek felt rug, showing

how shaped pieces of red and blue felt are joined together

to form the whole. |

Activity

Find out how to make felt. Make a 20 cm x 20 cm sample of

a felt rug. You may like to dye the fibres using natural

dyes. Look carefully at the detailed photos of the Lakai

Uzbek felt rug, Figures 9 and 10. Design a pattern for your

sample reflecting Central Asian culture. Select and apply

suitable fabric decoration, perhaps embroidery, to enhance

the design.

|