|

The rivers that began in the mountains of Central Asia filtered

down onto the plains and created oases. Towns sprang up

at these oases as the Silk Road trade grew and flourished.

Travellers stopped for water, food and shelter and traded

with the oasis dwellers; in this way goods and ideas were

exchanged along the length of the Silk Road. The major urban

centres, like Bhukara and Samarkand, were organised as states

or khanates and were headed by a khan or chieftain. The

settled oasis dwellers were agriculturalists who produced

a range of agricultural goods, including grains, fruit,

nuts, cotton and silk. Many were also skilled craftspeople,

producing metalware, ceramics, and textiles such as ikats

and embroideries. These urban products were traded in the

bazaars for the nomads' animal products; meat and cheese,

and wool rugs and carpets.

Textile

arts of the urban oasis dwellers

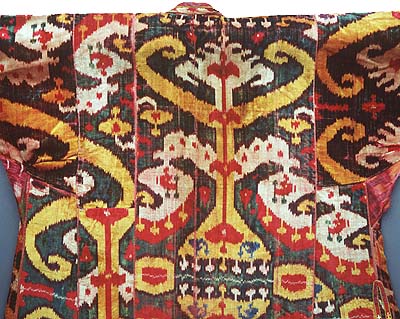

Ikats

Among the best known textile arts produced in urban centres

of Central Asia are ikat-dyed silk, and silk and cotton robes

and panels. They were produced by men in workshops. As you

could see from the timeline, silk

made its way from China into Central Asia via the Silk Road

and was embraced by the settled artisans.

Pardah

(wall hangings) and men's and women's clothing were predominantly

made using ikat silks or abr (meaning cloud). To

make ikat, which is known locally as abrbandi, warp

threads are tie-dyed before weaving giving the distinctive

streaky appearance. There are two main types of ikat in

Central Asia:

- full

ikat: the entire warp is tie-dyed and the order of the

threads is set at the time of dyeing

- strip

ikat: long skeins are tie-dyed and the pattern is determined

by the way these are positioned on the loom, often alternating

with plain warps. (Sumner, 1999:30)

Clothing

All over Central Asia, men, women and children wear basically

the same thing: shirt/dress and trousers under a coat and

a hat. In the urban centres

…

ikat-patterned khalats were worn by both men

and women, mostly for ceremonial and ritual use…The

cut of these brightly coloured robes varied very little

but the materials they were made of, the structure of

the fabric and the manner of ornamentation were all

indicative of the wearer's status. The lowest ranks

wore robes of adras (silk and cotton), while

the highest wore silk velvet ikat, sometimes embellished

with goldwork embroidery. (Sumner, 1999:31)

An

essential part of Islamic women's dress was the paranja,

which is a veiling garment worn over the head. Strict adherence

to custom required that the hair and faces of women were

not seen in public.

Fig.

3 Detail of Man's khalat

Silk ikat velvet, embroidered cuffs, printed-cotton

lining, woven by Uzbek men in ukhara, about 1870. 1220

x 1425 mm 85/1439

Powerhouse Museum Collection. |

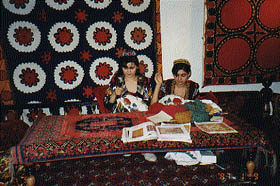

Embroidery

The other well known urban textile art of Central Asia is

the suzani. These are a range of silk on cotton embroidered

hangings of different sizes, featuring flowers or cosmological

symbols. Suzanis were used as wall hangings, bed covers

and room dividers and were made by women as dowry textiles.

Once a daughter was born, the women of the family began

to embroider suzanis for her dowry. The design was

drawn on the cloth by a senior woman of the family and embroidered

by several women. Once the embroidery was complete, it was

reassembled. Two of the main centres for these embroideries

were Bukhara and Samarkand, in what is now Uzbekistan.

The most common stitches were:

- chain

stitch, and

- basma

or Bukhara couching for filling.

|

|

|

Photo:

Christina Sumner

|

Photo:

Christina Sumner

|

Activity

- Read

the text on nomadic life. Identify the key factors affecting

the life of a nomad.

- Print

out the map of Central Asia and track the events identified

in the timeline on the map. The timeline

summarises the historical events and significant developments

in Central Asia and surrounding cultural centres.

|