|

Nomads were, and still are, dependent economically and physically

on their herds of animals. For transport, they relied primarily

on horses and camels. As a result, camels, and horses in

particular, were highly valued. This is 'reflected in the

wonderful array of woven and embroidered decorative trappings

used to ornament the animals – shaped blankets and

saddle covers, flank trappings, head and rump harnesses,

knee pads and, for Turkmen horses, special silver and carnelian-studded

leather horse jewellery.' (Sumner, 1999:28)

Herds

The only way for people to survive in this arid region was

to move with their herds of sheep and goats from place to

place each season. This became possible in the third millennium

BC when nomads began to use horses as transport, and importantly

they learned to ride horses. Camels were also used for transport,

and herds of sheep and goats grazed and moved with the nomads

on their seasonal travels to find good grazing. Sheep and

goats provided both food and drink and wool for clothes,

rugs, wall hangings and furnishings.

It

has been estimated that each nomadic family unit needed

about 100 kilograms of wool a year to make their own

clothing and felts, which is roughly equivalent to a

hundred large, thick woollen sweaters. (Sumner, 1999:24)

This website has been archived and is no longer updated.The content featured is no longer current and is being made available to the general public for research and historical information purposes only.

|

|

Photo:

Julie King

|

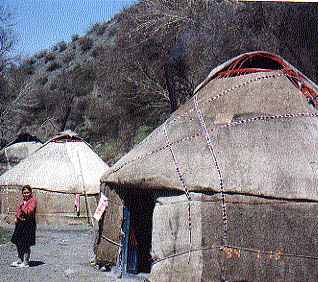

Yurts

In addition to horses and camels, portable homes (the felt

yurt) were vital to the nomadic lifestyle. The yurt allowed

the nomads to survive in very cold weather. This portable

lifestyle meant that art and creativity were expressed in

the rugs, furnishings and clothes which were also portable.

Setting

up and transporting the yurt

The yurt consisted of between five and eight sections of

willow-wood lattice tied together to form a circular frame.

A space was allowed for a doorway, which traditionally faced

east. More wooden slats locked into a small, circular frame

at the top to form the roof. This allowed the yurt to be

collapsed, transported and set up with ease. Women could

set up a yurt completely in just two to three hours. Three

camels were needed to transport the yurt and the family's

household possessions.

|

|

Photo:

Adrienne Cobby

|

Textile

products for the yurt

A broad woven band was tied round the middle of the yurt

to stabilise it. For special occasions, such as weddings,

ceremonial bands were brought out and wound around the yurt.

Thick, shaped felts held with woven ropes formed the outer

walls and roof. The inner walls were made from woven reeds

or lined with printed cottons. The ground inside was covered

with felts; pile carpets and flat-woven rugs (kilims)

which featured beautiful patterns and rich earthy colours

were placed on top.

|

|

Photo:

Adrienne Cobby

|

Areas

inside the yurt

The yurt was divided into areas for cooking and living.

The cooking area of the yurt was on the right and was considered

to be the women's area. The men's area was to the left and

often housed the riding equipment. If the household was

more affluent they may have had separate yurts for cooking,

producing rugs and entertaining visitors.

|

|

Photo:

Adrienne Cobby

|

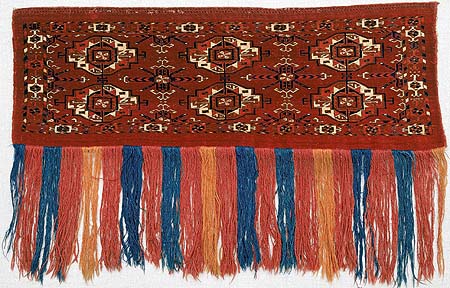

Household

goods were stored in carved wooden boxes or woven bags (juval,

torba etc.) strapped to the lattice. See Fig. 2 Tekke Turkmen

torba.

Fig

2. Tekke Turkmen torba

Small

bags like this were suspended from the wall of the nomads'

yurt (tent) and used to store household items. The major

(large) gul, geometric motif, is of a type often seen

on Tekke torbas, while the minor (small) gul occurs

in different forms in a range of weavings.

Wool warp and weft, wool and silk, asymmetrical knots,

made in north-western Afghanistan, about 1900. 1520

x 1030 mm. Powerhouse

Museum Collection 96/391/1,

purchased with the assistance of the Oriental Rug Society

of NSW, 1996. |

Clothing

The everyday clothes of the nomads were functional and attractive.

Their ceremonial dress in particular is noted for its beauty.

…

the densely embroidered chyrpys (silk coats) with long

false sleeves worked by Tekke Turkmen women until the

early 1900s… had different coloured ground cloth

depending on the age and marital status of the woman

wearing them and were worn for special festivals. They

are still made, but without the false sleeves and with

less embroidery. (Sumner, 1999:28)

Survival

of the nomads

To survive as nomads groups needed:

- safe

routes

- good

grazing land

- a

ready supply of water

- sufficient

wealth to own the necessary equipment.

However,

even with all this, nomads were subject to the extremes

of weather, the violence of other tribes and the threat

of wild animals. Life as a nomad could be far from idyllic.

From

the initial domestication of the horse as a riding animal

to the Manchu conquest of China in 1644 CE, the nomads

of Central Asia have interacted, often violently, with

the cultures that surround them. The first wave out

of the Caucasus, the Indo-Europeans, set the pattern

of raids, invasion, settlement and eventual blending

into the local civilisation. (Sumner, 1999:10)

Often

this resulted in nomads moving to more fertile land and

settling. Even so there were always plenty of other nomads

to take their place. 'Settlement demands order, control

and planning; nomadism requires flexibility, mobility and

opportunity.' (O'Bannon, 1998: 10)

The

interdependence of nomads and oasis dwellers

Although at times there was conflict between the nomads

and oasis dwellers, the oasis cities relied on nomads for

animals and animal products such as wool, leather and meat.

The nomads depended on the oasis dweller for agricultural

food products, silk and cotton threads, textiles and the

products of craft workshops: metalwork, woodwork and ceramics.

During

times of relative peace and prosperity, direct trade

also took place between the nomads and the major civilisations:

Greece, China, Iran, Byzantium. At annual border-town

fairs luxury items, tools, household goods and agricultural

products could be exchanged for fine horses and furs,

wool and leatherwork and sometimes goods stolen in raids

on caravans or distant cities. Because of the breadth

of the nomad range, they acted as a means of transmitting

arts and ideas from the borders of China to the heart

of eastern Europe. (Sumner, 1999:11-12)

|