|

Indigenous

Australians and the Snowy

The Snowy River and its hinterland have sustained humans

for thousands of years. Before European colonists went

to the region in the early 19th century, the Indigenous

Ngarigo, Walgalu and Southern Ngunnawal people lived

and interacted in the region. They fished in its waters

and hunted game in the surrounding countryside. Around

Jindabyne, the river rocks were used extensively for

tool making. Men and women had separate sacred water

holes for purification ceremonies. In the warmer months

people would travel to the high country to feast on

bogong moths.

| This

photograph taken by Charles Kerry around 1890 shows

Boona, a Ngarigo woman from the Monaro region which

surrounded the Snowy River. She was referred to

as a Queen of the Manero by whites. Although

the title did not accurately reflect Aboriginal

tribal hierarchies, it may well have indicated that

she held a significant place within her tribal group. |

Photo: Boona of the Cooma Tribe

by Charles Kerry. Tyrrell Collection, Powerhouse

Museum. |

The

Snowy in the 19th century

From the 1820s Indigenous people were gradually dispossessed

as colonists from Europe and Asia arrived. Polish explorer

P.E. Strzelecki was among the first Europeans to explore

the area. He named Mount Kosciuszko, Australia's highest

mountain, after Tadeusz Kosciuszko (1746-1817), an engineer

and soldier. By the end of the 19th century the Ngarigo

and Wolgal population had dwindled as a result of disease,

violence and dispersal.

|

The

river took on a different significance for the

colonists who now occupied the area for grazing,

farming and gold mining. Exotic trout were introduced

from the late 1880s and within a decade the Snowy

had become renowned for its sport fishing. Most

notably, the area became associated with the emerging

national mythology of the Australian bushman,

following the publication of Banjo Paterson's

poem about the exploits of the high country stockman,

The man from Snowy River, in 1895.

This

photograph titled Glimpse on the Snowy River,

was one of several images of the river taken by

prolific commercial photographer Charles Kerry

around the time that Paterson wrote his poem.

|

Photo: Glimpse on the Snowy River

by Charles Kerry. Tyrrell Collection, Powerhouse

Museum |

A

wasted resource?

Despite its mythologisation, the Snowy River was also

regarded by many non-indigenous Australians as a wasted

resource because it flowed to the sea through country

that was already well watered. Proposals to divert the

river for irrigation and power generation were presented

from as early as the 1880s but it was not until the

1940s that the necessary resources and technological

capacity were realised with the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

The Snowy River was finally dammed twice: first at its

headwaters at Island Bend in 1965, and again downstream

at Jindabyne in 1967.

After

Lake Jindabyne was created, 99% of the river's water

was retained and diverted for power generation and irrigation.

In October 2000 however, the NSW and Victorian governments

with the Federal government, agreed to a program to

return 28% of the river's former flow by 2010.

Impact

on the environment

Activity

The Snowy Mountains Scheme has resulted in enormous

environmental upheaval and change. The impact on the

environment is a complex issue to assess. There are

at least two different points of view to consider. Read

the material below and summarise in a list the positive

and negative impacts.

Environmental

and social costs

The contradictory view of the Snowy River as both a

cherished landscape and a resource to be exploited,

has characterised white Australian attitudes towards

the river to the present day. Groups such as the Snowy

River Alliance campaigned vigorously in the 1990s to

restore more of the river's flow. They argued that with

only one percent of its original water, the ecology

of the river was collapsing.

Those who lived down stream from the Jindabyne Dam were

compelled to find alternative sources of water. These

people had been told that the Scheme would stop spring

flooding. After the damming of the Snowy, they struggled

to get enough water for domestic and commercial use.

Significantly

campaigners bolstered their arguments by emphasizing

the river's heritage significance as the 'birthplace'

of the Man from Snowy River. In 1998 they organised

a protest on the banks of the Snowy at Dalgety featuring

Tom Burlinson, the actor who had played the Man from

Snowy River in the 1980s telemovie. The river, it was

argued, was as much a 'national cultural icon' as it

was a ecological system to be restored.

|

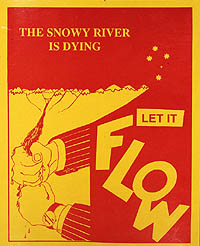

This

‘Save the Snowy’ poster was one of many

produced by the Snowy River Alliance to publicise

the plight of the river. Through meetings, petitions,

and political lobbying they have managed to make

their case a significant issue in the press and

parliament.

Environmental

concerns were not confined to the Snowy River

in the east. Critics of the Scheme also pointed

to the waste of water that occurs through evaporation

and seepage along its route from east to west

and authority over its management shifts from

the Authority to other state bodies. Dry land

salinity in the western farnlands, resulting from

the rising salt table caused by excessive irrigation,

was another major concern.

|

Courtesy: Snowy River Alliance

|

Environmental

and social benefits

The Snowy Mountains Scheme provides about 74% of available renewable

energy on the eastern mainland Australian electricity grid and 28% nationwide. This represents a

displacement of more than 5 million tonnes of 'greenhouse

gases' that contribute to global warming every year.

As hydro-generated energy it does not pollute the atmosphere

and as it is part of the water cycle, it is renewable.

Unlike other renewable energy sources it is easy to

store and the water can be used several times as it

passes through a series of power stations. In addition,

the Scheme's scenic lakes and reservoirs are used for

recreation by hundreds of thousands of visitors each

year.

The water diverted westward from the Snowy, Tumut and

other rivers by the Scheme, contributes to the Murrumbidgee

Irrigation Area in the dry inland of NSW. Farmlands

irrigated by the Snowy water produce millions of dollars

worth of crops every year, for the national and international

markets. Irrigation sustains dozens of agricultural

communities in this region of Australia. In 1968 an

entire town, Coleambally, was created as a result of

the new flow of water

Rhona

Morton, pictured here, and her husband Les moved to

a farm in the Coleambally area in 1964. They lived in

this caravan and a shed for 2 years while building a

house. It took several years of work before the farm

returned a profit.

Photo: courtesy L and R Morton

|

Irrigated

crops

The irrigated fruit and grain crops produced in western

NSW are worth millions of dollars annually. This photograph

shows irrigation canals at a citrus orchard in the Riverina.

Photo: Gregory Heath, courtesy CSIRO

Land and Water, Griffith Laboratory.

|

Rice

is the main summer crop in the Murray and Murrumbidgee

valleys of western NSW. Fields, like this one, remain

flooded for 4-5 months and therefore need large amounts

of irrigation water. Rice is a significant export crop.

Photo: Gregory Heath, courtesy CSIRO

Land and Water, Griffith Laboratory.

|

The

Snowy Water Inquiry

An

inquiry was set up into the flow of the Snowy and hundreds

of submissions were received locally and from further

afield. The inquiry found that restoring 30% of the

Snowy flows was not economically viable. It recommended

instead 15% along with improvements to irrigation pratices

in the west. The balance of power shifted markedly in

1999 when a local pro-river independent candidate for

the Victorian parliament, Craig Ingram, defeated the

sitting National Party member in the State election.

Along with two others he held the balance of power after

a landslide vote against Jeff Kennett’s coalition

government. Ingram’s newfound power was instrumental

in getting Victoria and NSW to commit to funding better

irrigation practices including the enclosure of canals

to stop evaporation in order to return flow to the Snowy.

The accompanying commitment to restore 28% of the river’s

flow was hailed by farmers in the east and conservationists.

The

fight was bitter because, as the Commissioner of the

Water Inquiry Robert Webster noted, restoration of flow

to the Snowy pitted three Australian icons against each

other, the river which had been immortalised by Banjo

Paterson's poem; the Snowy Mountains Hydro electric

scheme which generates clean electricity and was arguably

the seat of Australian multiculturalism; and the food

bowl of the farmlands of the Murray and the Murrumbidgee,

irrigated by additional flows from the Snowy. However

the result is evidence of the increased questioning

of dry land irrigation and dam construction in Australia

and is potentially one of Australia’s most significant

cases of environmental rehabilitation.

Activity

1. Read the following articles about the future of the

Snowy River.

Bonyhady, T. (2000) Old man icon, Sydney Morning Herald,

May 20, 6S.

Condon, M. (2000) Roaring glory, The Australian Magazine,

October 14-15, pp 16-20.

2. Visit the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority

www.snowyhydro.com.au/environment/report.pdf web-site

to download a PDF file of the document Meeting the environmental

challenge (1999).

Impact

on society

Lost places

The creation of the huge Eucumbene, Jindabyne, Blowering

and Jounama reservoirs resulted in the flooding of thousands

of hectares of land. Two whole towns, Adaminaby and

Jindabyne, and numerous farms and homesteads were inundated.

Thousands of years of Aboriginal history were also lost

beneath the waters. Both Adaminaby and Jindabyne were

rebuilt nearby as new towns that were heralded as modern

and comfortable. People were compensated by the Authority

for their losses and relocated.

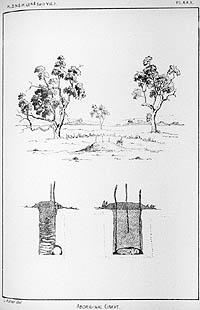

| Aboriginal

people from around Tumut and the Monaro lost their

land to European colonists long before the Snowy

Mountains Scheme started. Those remaining by the

end of the 1800s were moved off to missions and

reserves. They left many objects and sites of social

and spiritual significance. Some were recorded before

land was flooded for the Scheme, others remain unknown.

These places and objects are lost to descendants

of the original inhabitants and to the country.

This 19th century Aboriginal grave near Jindabyne

was recorded by anthropologist Richard Helms in

his article 'Anthropological Notes', Journal

of Proceedings of Linnaen Society, 1895. |

Illustration of 19th

century Aboriginal grave from

Richard

Helms 'Anthropological Notes' 1895. |

| Sixty

years later Dom Rankin took this photograph of his

family home in Jindabyne with a Box Brownie camera.

It was the last time he saw his family home. When

the photograph was taken, the building had already

been sold to the Authority and was demolished shortly

afterwards. |

Photo: Dom Rankin

|

New

towns

Some people were happy with their compensation and the

prospect of moving to a modern town, but others grieved

at giving up their homes in the national interest.

This grief, writes historian Peter Read, is for "lost

places" and "lost roots, lost childhood or

a lost community". The new Adaminaby, located several

kilometres away from Lake Eucumbene, suffered from physical

and economic isolation. The new Jindabyne, however,

has flourished partly as a result of its proximity to

Lake Jindabyne, which provided a new identity and source

of income. (Read, 1996: 75-100)

Many

other properties across the Blowering Valley were flooded

with the construction of the Blowering and Jounama Dams

in the 1960s. These included Talbingo Station, the birthplace

of renowned Australian writer Miles Franklin. Jack Bridle's

family moved to the valley in 1848. Jack, a local historian

and poet, was born at a nearby settlement but arrived

at Blowering as a boy in 1921. After the dams were built

Jack Bridle farewelled his valley in a poem that

highlights the association of place with personal identity

and family and community history.

Snowy

Scheme kids

Thousands of children grew up around the Snowy Mountains

Scheme. Many, of course, were local children. They saw

their towns change with the development of the Scheme.

Others came to the area because one or both parents

found work there. They lived in large established towns

like Cooma or construction townships such as Cabramurra

and Eaglehawk. Many others were born on the Scheme.

The

presence of so many children changed the shape of existing

towns. Recreational facilities, schools and baby health

centres were required and were built by the Authority

or the major construction companies. At Jindabyne, for

instance, the Authority provided a school building.

At Cooma it subsidised the construction of a public

pool.

Cooma public pool. Photo: Bayram

Ali (Powerhouse Museum Collection)

|

The

Snowy was a unique place to grow up because of the climate,

the social mix and the mobility of many of the families.

Children learnt to ski for fun and out of necessity.

The photograph below shows boys practising ski jumping

at Cabramurra, in the late 1950s. Cabramurra is the

highest town in Australia and during the years of the

Scheme it hosted many skiing events.

Photo: Bayram Ali (Powerhouse Museum

Collection) |

Some

immigrant workers brought children with them from overseas.

While they often went through the difficult experience

of being different from local children in language,

dress and custom, the presence of so many different

cultures also helped overcome such problems. The photograph

below shows boys at Eaglehawk standing with a soccer

ball on the township's playing fields. An organised

game for workers proceeds in the background. Soccer

was a relatively uncommon sport in regional NSW in the

1950s but it was popular with migrant workers and their

children.

Photo: Bayram Ali (Powerhouse Museum

Collection) |

Kalev

Tarmo, son of an Estonian worker, lived high in the

mountains at Happy Jacks village. He commented on the

effect of the experience on growing-up:

We

became different to a lot of other children. We found

we could be on our own longer and be more independent,

and the friendships seemed to be more binding. We

subscribed to a lot of periodicals and radio was a

big thing. (McHugh, 1989: 200)

Australian-born

Chris Griffiths recalled his childhood at Tumut:

We didn't really think it was any different from anywhere

else... In winter you'd go visiting the other houses...

their parents might be French so you'd have French

tucker. The next lot might be German and they'd have

all these knick-knacks lyin' around… that's what

was interesting. (McHugh, 1989: 201)

Families

often moved from one construction township to another

as projects were finished and others commenced. The

settlements were often divided by work status into precincts.

In Cooma, for example, children of wages or trades personnel

went to Cooma East school, while the children of salaried

or professional staff went to Cooma North school.

A

Multicultural workforce

When the Scheme began in 1949, there was a shortage

of scientific and engineering skills to meet the challenges

posed by the project. A massive national and international

recruitment programme was carried out. Migrants from

many countries with skills in surveying, tunnelling,

geology, hydrology, and transmission-line installation,

came to Australia to work on the Scheme.

Australians

worked alongside people from over 30 different countries

like Great Britain, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Italy and

Norway.

All

strata of society were represented, from the inhabitants

of historic centres of culture like Vienna and Budapest,

Berlin and Paris, to those living in remote villages

in the Balkans and Ukraine in conditions not far removed

from feudal times. (Raymond: 1999: 60)

The

Snowy Mountains Scheme is often portrayed as the start

of multiculturalism in Australia because of the intensity

and success of its cultural mix. This claim tends to

obscure a long history of cultural diversity across

Australia. From Broome in the north of Western Australia

to Melbourne in the south east of the continent, there

were many examples of different peoples living, working

and socialising together before the initiation of the

Scheme.

|

Contract

workers

Many

of those who came from overseas were employed

by the large contracted firms from Norway, France

and the USA. Having completed their work they

returned to their country of origin.

The

Schemes's first operational dam, tunnel, pressure

pipeline, turbo-generators and transformers were

built by Norwegians from the firm Selmer Engineering

Pty Ltd using technology from the British firms

English Electric Co. Ltd and Hackbridge and Hewittic

Ltd. The picture on the right shows Norwegian

tunnellers at Guthega in the early 1950s. Most

of this workforce returned to Norway after completion

of the project.

|

Photo: SMA

|

|

Refugees

Other Snowy workers arrived in Australia as refugees

from postwar Europe. Australia took 180 000 'Displaced

Persons' between 1947 and 1951. Typically these people

had lost their homes during the war or had left their

countries after Communist regimes were established.

In Australia they were required to work for two years

in assigned jobs in return for refuge. Some were

sent to the Snowy, others made their way there after

serving their two years elsewhere.

Unassisted

immigrants

By far the largest group of overseas-born Snowy workers

arrived in Australia as unassisted immigrants, part

of the nearly 2 500 000 people who came to Australia

between 1947 and 1974. Some of these people had heard

of the Scheme before they left their homelands, others

moved to the Snowy in search of work after they arrived.

Most

were of European origin because the White Australia

policy discouraged Asian and coloured immigration.

However Australia was still very different to countries

left behind. As a result these people both adapted to,

and changed, their new communities.

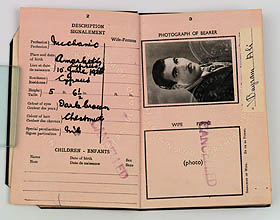

Bayram

Ali was one of the unassisted immigrants who found his

own way to the Scheme after coming to Australia. He

arrived from Cyprus in 1949 with his passport. Because

Cyprus was then a colony of Great Britain, Ali carried

a British passport. As Australia had close cultural,

political and economic ties with Britain, he was not

regarded as an alien.

Bayram Ali. Powerhouse Museum Collection

|

Becoming

Australian

Through

the 1950s and much of the 1960s, Australia's immigration

policy was guided by the ideal of assimilation. 'New

Australians' were expected to fit in with existing Anglo-Celtic

customs and traditions. In 1952 Immigration Minister

Harold Holt spoke of building 'a truly British nation

on this side of the world' by imposing these customs

on migrants.

Between

1948 and 1983, British and Irish migrants received citizenship

rights - which included the right to vote - after five

years residency. Others had to be 'naturalised'. This

process involved swearing allegiance to the British

monarch.

Queen

Elizabeth's portrait is prominent at this citizenship

ceremony in Cooma in the early 1960s. Photo: Bayram

Ali (Powerhouse Museum Collection)

Queen

Elizabeth's portrait is prominent at this citizenship

ceremony in Cooma in the early 1960s. Photo: Bayram

Ali (Powerhouse Museum Collection)

|

The photograph above shows a naturalisation ceremony

in Cooma in the early 1960s. The portrait of Queen Elizabeth

II is visible at the back of the stage. It also appeared

on naturalisation certificates. However, the woman addressing

the crowd is Tanya Verstak the first non-Anglo

Miss Australia. Her presence suggests a shift in attitudes

towards migrants and the acceptance of cultural diversity.

In 1959 the town of Cooma built an avenue of flags in

its main park to acknowledge the contribution of different

nationalities to the Scheme. An International Club was

established to celebrate different cultures and public

debates on the place of migrants in Australian society

were held.

Despite

the emphasis on assimilation, migrants did not abandon

their cultural practices and beliefs. Anti-communist

workers, from Balkan states in particular, frequently

removed the communist Yugoslav flag in the avenue of

flags. Attempts to reinstate the flag were eventually

abandoned.

|

This German carpenters' guild scarf was brought

to Australia by Karl Rieck. Like his colleagues,

Karl wore his traditional carpenter's costume

of black corduroy while working at Island Bend,

in deference to his native country's guild rules.

The German carpenters were among the most distinctive

groups on the Scheme.

Lutherans

established a congregation in Cooma and built

a church that continues to service their community.

Delicatessens and restaurants offering a range

of foods for the new European communities opened

in Cooma and Tumut where previously there had

been only traditional Anglo-Australian cuisine.

|

Photo: Sotha Bourn

(Powerhouse Museum Collection) |

Snowy

workers from Norway, Czechoslovakia, Italy and Germany

helped to develop the small Australian skiing industry.

Kore and Eva Grunnsund followed in the footsteps of

an earlier Norwegian immigrant, Martin Amundsen, who

introduced new skiing technologies and techniques to

Australia in the 1880s. Czechoslovakian born Tony Sponar

helped to establish Thredbo as a major tourist resort.

The photograph below shows a ski jump built at the authority

town of Cabramurra. The event is probably the NSW and

National Championships of 1961, which featured ski jumping,

slalom and langlauf (cross-country) events.

Photo: Bayram Ali (Powerhouse Museum

Collection) |

|