|

The

qipao is recognised by most people as the classic

Chinese garment for women. Qipao is a Mandarin word

which means Manchu banner robe. Judging from

its name, the qipao originates from Manchu dress

of the Qing dynasty. It was a simple garment, essentially

made from two pieces of cloth cut to follow the form

of a woman's body, with slits at the sides to allow

for ease of movement. It was an extremely versatile

garment that could be made from any sort of fabric,

to different lengths and with long or short sleeves.

Many people will be more familiar with the Cantonese

term for the garment which is cheungsam, meaning

long shirt.

Cheungsam

gallery

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

Photo courtesy: Wang family.

|

|

Photo courtesy: Wynne Shih.

|

Political,

economic and social change

The early twentieth century was a period of political,

economic and social change. Increased contact with the

West, through trade, resulted in an exchange of culture

and ideas. This was a significant time for women.

A

new Western concept was that of gender equality, and

this encouraged community leaders in their campaign

for women's freedom: to receive an education, to choose

a career and determine their marriage partners. Educated

women and those from wealthy families took the opportunity

to experiment with these new possibilities. (Roberts,

1997: 55)

The

cheungsam - which was born alongside a growing

awareness of women's rights - symbolised this transition.

It is significant that Chinese women, after being

released from such restrictive traditions, selected

the cheungsam as their national dress. The

women portrayed on the calendar posters dressed in

sleeveless cheungsam with high side-slits,

illustrate one aspect of women's new found freedom.

(Roberts, 1997: 64)

Advertising poster for Qidong Tobacco

Company showing a fashionable woman wearing a cheungsam.

Colour lithograph by Hang Zhiying, made in Shanghai,

China during the late 1930s. Powerhouse Museum collection.

95/29/2 |

The

centre of Chinese fashion at the turn of the century

was the coastal city of Shanghai. A leading and prosperous

metropolis in China before World War II, Shanghai

had such a reputation as a centre for women's fashion

it was called the Paris of the East. The evolution

of the cheungsam in Hong Kong, along with other

cities in China, kept abreast of the trends in Shanghai.

The earliest style of cheungsam was loosely

fitted and ankle length. Over time, hem lines rose

to mid-calf or knee length. Sleeves varied, from long

to medium length to small capped sleeves, or a Western-style

frilled sleeve might be added. Some were sleeveless.

The stand collars were sometimes stiffened and could

go as high as the ears. The cheungsam became

increasingly tight-fitting and side-slits rose higher.

(Roberts, 1997: 59-60)

The

cheungsam was the most popular form of female

dress in Hong Kong from the 1930s to the 1960s. It has

remained popular with certain groups of women in Hong

Kong, Taiwan and in Chinese communities throughout the

world.

Although

the collar and right-fastening lapel of Manchu dress

are reflected in the cheungsam that's where the

similarity ends. The loose fitting styles and the extended

wide sleeves of late 19th century dress were quite different

to the form fitting cheungsam.

Fabrics

for cheungsam

The cheungsam was made from a variety of fabrics

depending on the season and the occasion:

| Silk |

Synthetics |

| Brocade |

Wool |

| Velvet |

Cotton |

| Lace |

Satin |

Silk

and cotton wadding and fur linings were also used.

Activity

Next to each fabric write the season and an occasion

it might be used for.

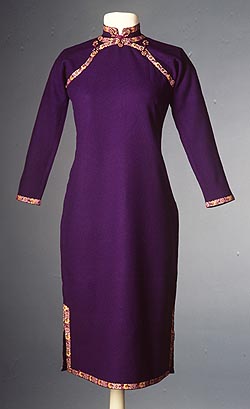

Woollen cheungsam, made in

Hong Kong in the 1940s. Powerhouse Museum collection.

97/167/5. Photo by Sue Stafford. |

Fabric

decoration

Indantren dye (originally from India) was widely used

for plain dyed fabrics worn more frequently by working

women. In addition to beautiful, high quality silk brocade

fabrics, more affluent women were able to have highly

decorated cheungsam featuring:

- embroidery

- sequins

- application

of trims.

Embroidery

patterns were initially traditional, featuring flowers

and symbolic motifs. As contact with the West increased

the influence was seen in the motifs.

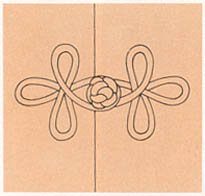

Toggles

Decorative toggles, known as huaniu, are made

to fasten traditional style qipao or cheungsam.

The knotted head is regarded as male and the pair with

an eye, female. Huaniu used for collars are usually

the same size whereas those used to fasten the right

of the lapel are different sizes; the smaller section

being sewn close to the shoulder.

While

the cheungsam has varied over time in shape,

colour, material and design features, one fundamental

element has remained the same: this is the knotted

buttons and loops generally known as huaniu

or panhuaniu, which are stitched to fasten

the collar and lapel. Huaniu may be a small

feature but they should not be overlooked: they represent

the soul of the cheungsam and provide a distinctive

Chinese character. Huaniu are the product of

thousands of years of traditional knotting craft and

the designs and compositions vary from the plain to

intricate. Traditional designs include floral, animal

and insect motifs, and auspicious symbols, such as

pomegranates and the Chinese character shou,

signifying fertility and longevity. Most huaniu

on cheungsam are designed to match the pattern

of the fabric and the colour of the braided trim on

the collar cuff and hem. (Roberts, 1997: 61-2)

Activity

1. Look at the huaniu used on the cheungsams

in the Cheungsam gallery.

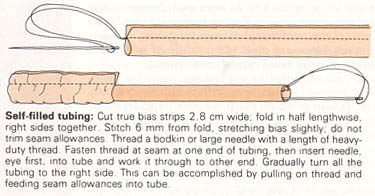

2. Use fabric scraps to create at least one huaniu

or as it is sometimes known, a frog and Chinese ball

button. To make these you will need to make some self-filled

tubing or rouleau.

Alternatively

create a paper scrolling picture to design a huaniu.

Courtesy: Reader's Digest (Australia)

|

Frog closure Courtesy: Reader's Digest (Australia)

|

|

Courtesy:

Reader's Digest (Australia)

|

Sewing

the cheungsam

The cheungsam has traditionally been made by

tailors, many of whom were trained in Shanghai, where

fine tailoring is a tradition. Shanghai tailors 'have

traditionally sewn the outerpart of the cheungsam

and the piping entirely by hand'. (Roberts, 1997: 66)

…

sophisticated skills are required in producing cheungsam

to fit customers of various body shapes and ages.

The garment could be so fitted that it was affected

by a change in underwear … body-hugging cheungsam…

could require as many as ten darts. (Roberts, 1997:

67)

Cheungsam

of the fifties and sixties

In the fifties and sixties the cheungsam was

the glamour garment - virtually everyone had at least

one. Different styles of cheungsam differentiated

one's class or profession. The 1960s movie The World

of Suzie Wong featured Suzie Wong wearing a mini

cheungsam.

Who

wears the cheungsam today?

By the end of the seventies few Chinese women wore the

cheungsam; it was mostly worn by:

- older

women 'usually with a Western-style jacket of matching

material for more formal dress' (Roberts, 1997: 63).

Many of these women go to the same tailor they have

used for years, the tailor has their measurements

and knows their preference for various fabrics.

- actors

and wealthy women still wear what some regard as Hong

Kong's national costume.

- school

girls comprise a large clientele for the cheungsam

tailor as a number of Hong Kong schools continue to

use it as the basis for their school uniform. The

uniforms are tailored for each student based on their

measurements but unlike the ones worn by the actors

it is loose fitting - more like the traditional male

long robe or cheungsam.

Qipao, wool, made

in Hong Kong in the 1950s. Private collection. Australia.

|

Students from the True Light Middle

School, Hong Kong, wearing cheungsam, 1996.

Courtesy: The True Light Middle School (Roberts,

1997: 68). |

The

cheungsam in the 21st century

After the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997 there

has been an increased interest in symbols of national

identity such as dress. Young designers and young people

in Hong Kong are wearing the cheungsam in new

and different ways. Charmaine Leung, a fashion designer

wears her off-the-peg cheungsam 'fitted and made

from traditional style silk brocade, in colours such

as red, black or dark blue.' with 'loafers, a cardigan

wrapped round her waist and backpack.' (Roberts, 1997:

73)

Charmaine Leung, fashion designer

and teacher, wearing a cheungsam, in January 1997.

Photo by Piera Chen. Courtesy: Dr Hazel Clark. |

|