Cochlear Implant

1983

bionic ear for profoundly deaf people

Some great ideas need enormous commitment and cooperation to bring them to fruition. Graeme Clark's father was a deaf man in a hearing family and society. He was a pharmacist and often had to ask his customers to 'speak up' about their medical problems - which embarrassed him and them.

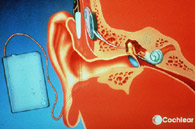

In 1967 Graeme embarked on a long journey towards fulfilling his dream of helping deaf people 'hear' the spoken word again. For ten years his research into electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve via an implant into the cochlea (a structure in the inner ear shaped like a snail shell) struggled along on animal experiments and university grant funding.

In 1974 a telethon on Channel 10 in Melbourne generated enough funds to take his work to the prototype stage and test it in a human patient, Rod Saunders. The 'bionic ear' worked: Rod could perceive sound again.

This demonstration encouraged the Australian government to finance commercialisation of the 'bionic ear'. The financing of the cochlear implant?s manufacture and marketing became a remarkably successful joint venture. The three-way partnership was between researchers at the University of Melbourne, the federal government and a medical equipment exporter called Nucleus. This partnership led to the formation of a string of Cochlear enterprises in the US, Japan and Switzerland including Cochlear Pty Ltd in Australia.

The NucleusŪ 22, introduced in 1983, was the first use of a 22-channel implant. This allows the user to distinguish a wide range of sound frequencies and is the world?s most widely used cochlear implant system. By the early 1990s Cochlear Pty Ltd was making a profit and Professor Clark was earning royalties.

In 1994, after 5 years of lobbying, the implant was approved by Japanese health insurance companies, opening up a market of up to 50 000 profoundly deaf people.

NucleusŪ 24 Contour, introduced in 1999, uses a pre-curved electrode. The electrode is made with the curved shape of the cochlea, improving the sound quality and simplifying surgery. Its speech processor incorporates the microphone and processor behind the ear, eliminated unnecessary wires. It won an Australian Design Award? in 2000.

By the end of the century there were over 24 000 Nucleus users in 50 countries worldwide, and the total time that all Nucleus systems had been in use was over 142 000 years (Nucleus implant years).

Who Did It?

Key Organisations

Cochlear Pty Ltd : R&D, design, manufacture

University of Melbourne : R&D

Nucleus Ltd : commercialised first implant

Key People

Graeme Clark : innovator, team leader

Paul Trainor : manufacturer

Reginald Ansett : Channel 10 owner (telethon)

Further Reading

The story of the bionic ear

J Epstein

Hyland House, Melbourne, 1989.

Sounds from silence: Graeme Clark and the bionic ear story

Graeme Clark

Allen & Unwin, St Leonards, 2000

Links

Powerhouse Museum HSC Online Resources Case Study

Cochlear Pty Ltd

East Melbourne Hearing

Research Centre. (Bionic Ear Institute, Cochlear Implant Clinic, CRC for Hearing

and Communication Research)

NOVA. Australian

Academy of Science

US documentary: Sound

and Fury

SBS Insight:

Aug 31 2000 'Sound Decisions'

Deaf World

Web articles

Australian Association of the

Deaf

Deaf Youth Online

More

opinions

Questions & Activities

Cochlear Implant

|